*featured image courtesy of Vocal Media

I’ve been stopped by the police three time in my life.

The first time it happened, I was a young woman driving at night in Washington DC after leaving the apartment of a high school friend. I wasn’t comfortable driving in DC during the day — I’m still not — so driving at night, in the rain no less, had my anxiety in over drive. Even though DC is laid out like a grid, I just cannot wrap my brain around the east/west named streets and the north/south numbered streets. The rectilinear layout has me wishing I’d paid more attention in 10th grade geometry.

Back then, I used my Nokia cell phone for emergencies only. MapQuest was my co-pilot, a heavy creased sheet of computer paper perched precariously in the cup holder to my right. Naively, I thought I could simply scan the directions in from the bottom to the top, reversing the lefts and rights, and navigate my way back to Maryland after my hang out.

Suffice to say, I’m no Magellan.

In the dark, the rain was spitting against my windshield as the red haloed lights from the traffic around me blinked on and off. While I traveled down some main thoroughfare, trying to make certain I hadn’t missed my turn, I rolled through a yellow light. I remember seeing the street sign for Constitution Avenue just before hearing the “whoop whoop” of a police siren. As the area around me lit up in red and blue. Not once did it occur to me that it was me who was being signaled, so I kept going. Again, “whoop whoop”, with the lights more insistent. I pulled over, a flicker of indignation flaring up when the police car glided in behind me instead of past as I had expected.

Growing up, when my parents talked to me about the police, it always came from a place of seeking them out if I were in any kind of trouble — separated from an adult or feeling threatened out in public. I don’t recall an explicit conversation about what to do (or what not to do) if I was ever detained by the police, aside from just “follow their directions”. I’m pretty sure everything I knew came from books or tv.

This was a time before the heightened pervasiveness of how people of color have to be super aware of everything when they are pulled over. This was before Sandra Bland, Brieaon King, and others whose names we know and we don’t know had suffered from DWB.

The officer approached my car. I rolled down the window and the officer asked me if I knew why he had pulled me over — Just like in the movies. I replied, “No, Officer. I don’t.” My voice sounded different in my own ears; I had code switched without even thinking about it. As I think about this situation all these years later, it surprises me to recall that the code switching was because I was dealing with an officer of the law. His race — he was African American — was not a factor. Maya Lewis, in her article “As A Black Woman, I Wish I Could Stop Code-Switching. Here’s Why.” expresses it very succinctly.

In other cases, often dealing with law enforcement, the ability to code-switch to Standard English, or presenting yourself “and behave in a way that [make you] a non-threatening person of color,” said Chandra Arthur, tech entrepreneur, can “be the difference between life or death.”

As A Black Woman, I Wish I Could Stop Code-Switching. Here’s Why. by Maya Lewis

He said, “Well, you ran the yellow light.” I apologized, saying that I hadn’t realized as I had been trying to orient myself and read the street sign so that I could find my way home. He looked at me and shook his head. “I see that you have AKA tags on your license plate.” He was referring to the license plate frame that identified me as a member of Alpha Kappa Alpa Sorority, Inc., the first black greek sorority in the nation. “I see that you have AKA tags; I would expect more from a woman of AKA.”

I blinked at him, not quite sure I had heard him correctly. Not quite sure if he was being funny or serious. Not quite sure if I should respond or if I should just swallow it or if I should or apologize, again. I honestly don’t even remember what I said. What I do remember was that he did not issue me a citation. He gave me a warning with explicit instructions to “not let it happen again” before directing me to the highway that would carry me home.

During that encounter, I was not fearful of my life, mores, I was fearful of what to expect. This was a great unknown. Up until that point, I had never had any encounters with the police save state troopers coming to talk to my elementary school class about stranger danger. I was more fearful of a ding on my driving record than anything else. The perfectionist in me couldn’t handle that. I could barely handle the warning. The chastisement that not only had I done something wrong, but that this stranger in a position of authority basically told me they were disappointed in me — made my stomach roil.

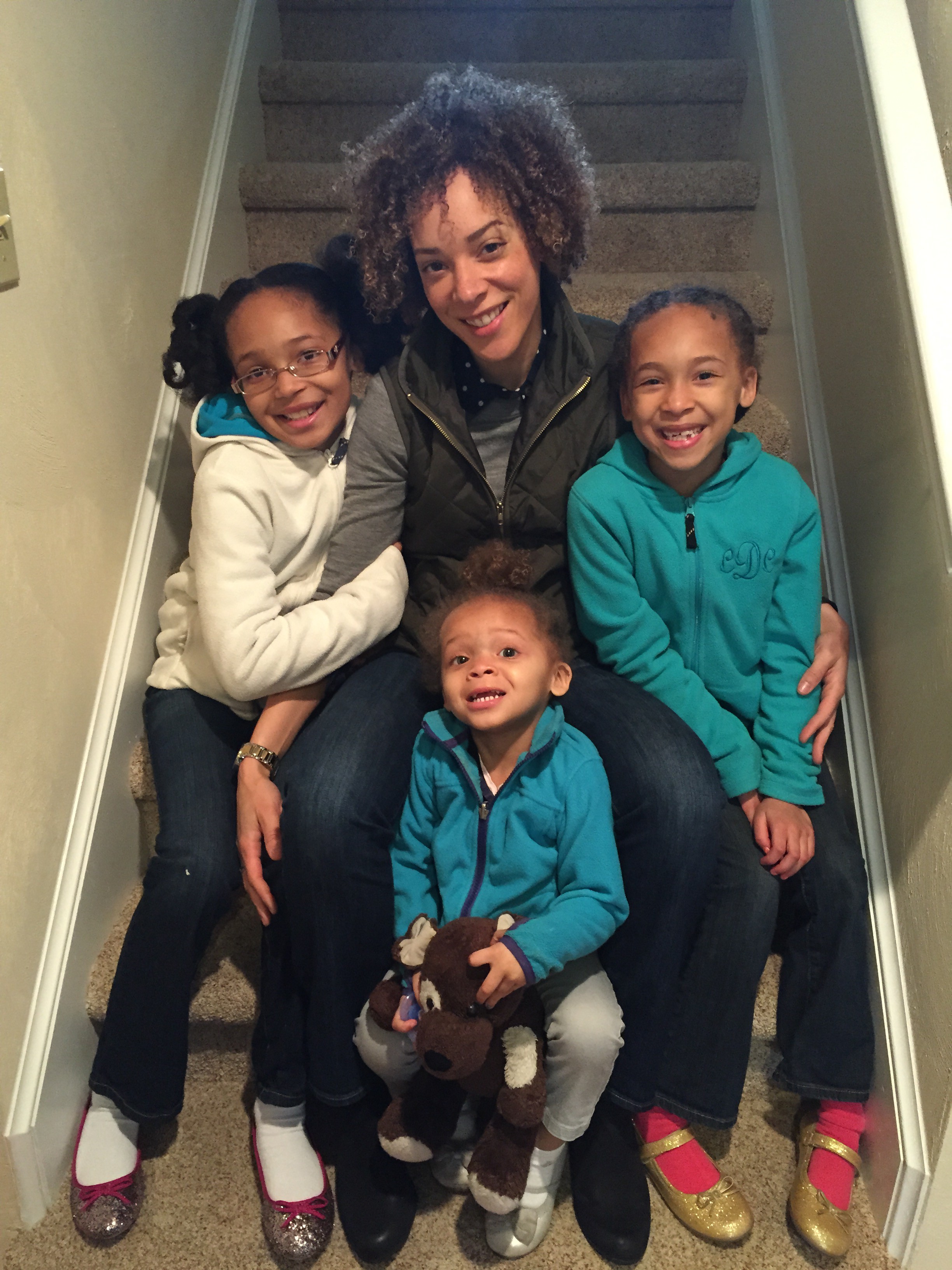

In the mid 2000s, I was pulled over again. The memory is years old, soft and blurry around the edges, but the recollection of fear and anxiety are as sharp as a paper cut. I remember rolling down Hampton Boulevard in Norfolk. Behind me, a three or four year old M safely tucked in her carseat. I can’t see C in this memory; she may have been just an infant, if she wasn’t still floating along in my belly.

Again, the siren and the lights.

Again, I kept driving, so certain that whatever the police needed to do had nothing to do with me.

Again, I was wrong.

When the siren chirped again, I slid off the boulevard into a residential neighborhood, the police close behind. I am older, slightly more savvy on how as a person of color, as a woman of color, I need to behave. My anxiety, an ever present co-pilot in my life, kicked on, but so did a little bit of fear. I had my child in the car. I didn’t know what I was being pulled over for and said as much to the officer — a female this time — when she asked me. I hadn’t been speeding. I hadn’t been on my phone. I wasn’t driving distractedly, fumbling with directions instead of focusing on the road.

The level of fear I felt at this particular time was greater than when I had been pulled over the first time. I can’t recall what my infraction, real or perceived, may have been. What I do remember is M crying. I remember trying to reassure her in between responding to the officer until she went back to her cruiser. I remember answering M’s questions: Why is the police officer at the window? What did we do wrong? Are you going to go to jail? Are they going to take me to jail?

She was frightened. Even though parents tell their children that police officers and firefighters are meant to help us, I don’t think we have the same fear associated with firefighters and EMTs that we do with the police. I assuaged whatever concerns she may have had, repeatedly assuring her that I was not going to jail, while instilling in her a level of respect and understanding of how one should conduct themselves in the presence of the police. I had no idea then that it would be the first of many such conversations that I would have with children as they grew.

As incidents of DWB have become more pervasive, so too have the discussions my husband and I have with our children about what it all means on a macro and micro scale. My daughters are 14, 12, and 7, so very young in my eyes, and yet they are grappling with very real issues about what it means to exist as a person of color in the world. We have had “The Talk” — the bare bones discussion of how they must carry themselves when they leave the sanctuary of our home. How they must be on guard. How they must use their “yes sir’s/ma’am” and “no sir/ ma’am”s. How they must keep their hands visible. How they must narrate their actions before moving a muscle. How they must remember these rules regardless of who else is in the car and how they are behaving. They are frightened, but they will remember.

There is no chapter about this in “What to Expect When You’re Expecting.”

I got stopped by a police officer last Tuesday afternoon. I was taking C and V to basketball practice and as is habit, I jumped the HOV lane to bypass the clogged roadways so that we could be on time. As we sailed down the road, I noticed the sign overheard, warning drivers against violating the HOV 3+ lane.

In Northern Virginia, the EZ-Pass electronic toll payment has a transponder with a toggle switch, allowing drivers to obtain toll-free travel on HOV roads when you have 3 or more people in your vehicle. Some people flip the switch without meeting the requirements and the police are cracking down. Fines of up to $1000 are imposed for these rule breakers. I don’t understand risking a $1000 fine for skipping on a $3.50 toll, but people have their reasons.

As I took our exit off the highway, I saw three cars on the shoulder ahead. Lights were flashing and a yellow vested officer was out of his car, walking into the middle of roadway. His both of his hands were up in a halting gesture. I began to slow down, but my brain surged in a million different directions. “Oh shit, was I speeding? I did come off the road a little fast, but so did the car ahead of me. Why is he walking towards me with his hands up? Where is the car that was in front of me? There’s no way he can tell that I’m Black from that far a distance. Can he? Where is my phone? Good, in the cupholder. Oh shit, my license is in my backpack in the back. Everyone has their seatbelt on, right?”

I had no choice but to stop, my hands automatically finding ten and two on the wheel. As the officer approached the passenger side where C was sitting, her hands immediately went palm down in her lap, clearly visible.

The tickle of fear I felt after crossing Constitution Ave, that itch of fear I felt on Hampton Boulevard, had blossomed into a full blown rash here on 495. What the hell is this? I didn’t do anything wrong.

Slowly, I lowered the window, just enough so that the officer could hear and be heard. He looked over at me, peering around the front seat, before asking how many people were in the car.

“Three, sir.” I said.

He looked at my transponder. He looked at C. He stuck his face closer to the window so that he could get a look at the interior of the car where V was reading Big Nate, completely oblivious.

“Okay,” he said. “Okay. You can go.” He backed away from the car a few steps before turning on his heel and going back to the shoulder. I rolled up the window as I accelerated the remaining length of the ramp. My eyes kept flickering to the rearview mirror to see if any cars behind me were stopped as well. None of them were.

“What just happened?” C asked as we idled at the light. “That was terrifying.”

“I know,” I said. “I think I just broke out in a flop sweat.”

“Me, too! The inside of my jacket is damp.” She went on to remark how she noticed the change in my posture, in my voice.

I wrestle with whether or not I’m grateful C was in the car with me so that she knows that the stories and examples we have given her and her sisters are not just stories and examples. She said herself, “I did everything that you and Dad told me to do. I put my hands in my lap. I sat up straight.”

My heart beats in alternating pulses like the red and blue lights atop a police car — pride in my child and fear for my child. That’s parenting in a nutshell, isn’t it?

I am exceedingly fortunate that my experiences with the police have been few and far between. Each were so fraught with anxiety, they felt massive in the moment, but in hindsight, they were minor.

A lot of uncertainty lies in between the revolutions of those flashing lights.